On Memory

And what then is memory, if not an interpretation of the past, for the benefit of the present and for the sake of the future?

Perhaps the past is an illusion, and there is only the present. But some deep current brought us here, and in the foggy before and after that bookends the now, there persists still a whisper of energy, a thin continuum we call memory. Memory helps us understand the past and prepares us for the future; it is the basis upon which we construct our identity. It is a lighthouse in the stormy sea of time.

This was supposed to be the essay where I took a break from writing about technology. But a notion, once lodged, is a mighty hard thing to dislodge. And so, in what was to be an exploration of memory, the technological lens through which we live our lives once again asserted itself. Oftentimes, I feel we are so steeped in technology that we forget it's there; like the fish who, when asked how the water is, replies, "what's water?".

Some years back, on my 40th birthday, my parents gifted me two items. From my mother, a scrapbook of life events, with pictures and captions going back to my great grandmother. A record of existence, so that I would know what my roots are, as I branch further into the world. She spent dozens, if not a hundred hours selecting, printing, labeling, and arranging the pictures to tell the story, searching her own memory for parts of the narrative. From my father, two pieces of petrified wood that had stood in his studio for the past four decades, which I used to take out and admire as a child. One which resembles a scarab, the other an irregular, squared triangle, with mineralized veins through which the ripple of the millennia had flowed.

And so these two memories took residence in my mind - one explicit, tied to faces and events, and one implicit, a symbolic representation of days gone by. I found myself reflecting on memory’s origins and its relationship to technology. When we consider an object - what are we speaking of? The physical manifestation born through weight, matter, and mass? The need for many men and machines to lift and transport it? Or the years and effort expended, the toil of time in service to that same thin continuum? Each object that we touch - does it hold the memory or do we? All memory can be lost in an instant; collective memory over the course of mere generations - an eyeblink in the cosmic vastness. Human memory exists with a certain degree of frisson, with the knowledge that were humankind to blink out tomorrow, so too would all human memory. To borrow from Keats, "Memory is energy, and energy memory - that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

There is a tale to be told that speaks to the relationship between our flawed, sublime, supremely individual human memories, and the unblinking, unflinching, technological memory afforded to AI – a digital memory that is, nonetheless, controlled by humans. Endowing technology with memory is to anthropomorphize it beyond its due, but it’s a useful model for exploration. Some human attributes, transposed to machines, don’t necessarily translate fully – memory is one of those attributes. This tale is one more chapter in the story of our unfolding relationship with technology, one that is now inextricably entwined.

Part I: Types of Memories

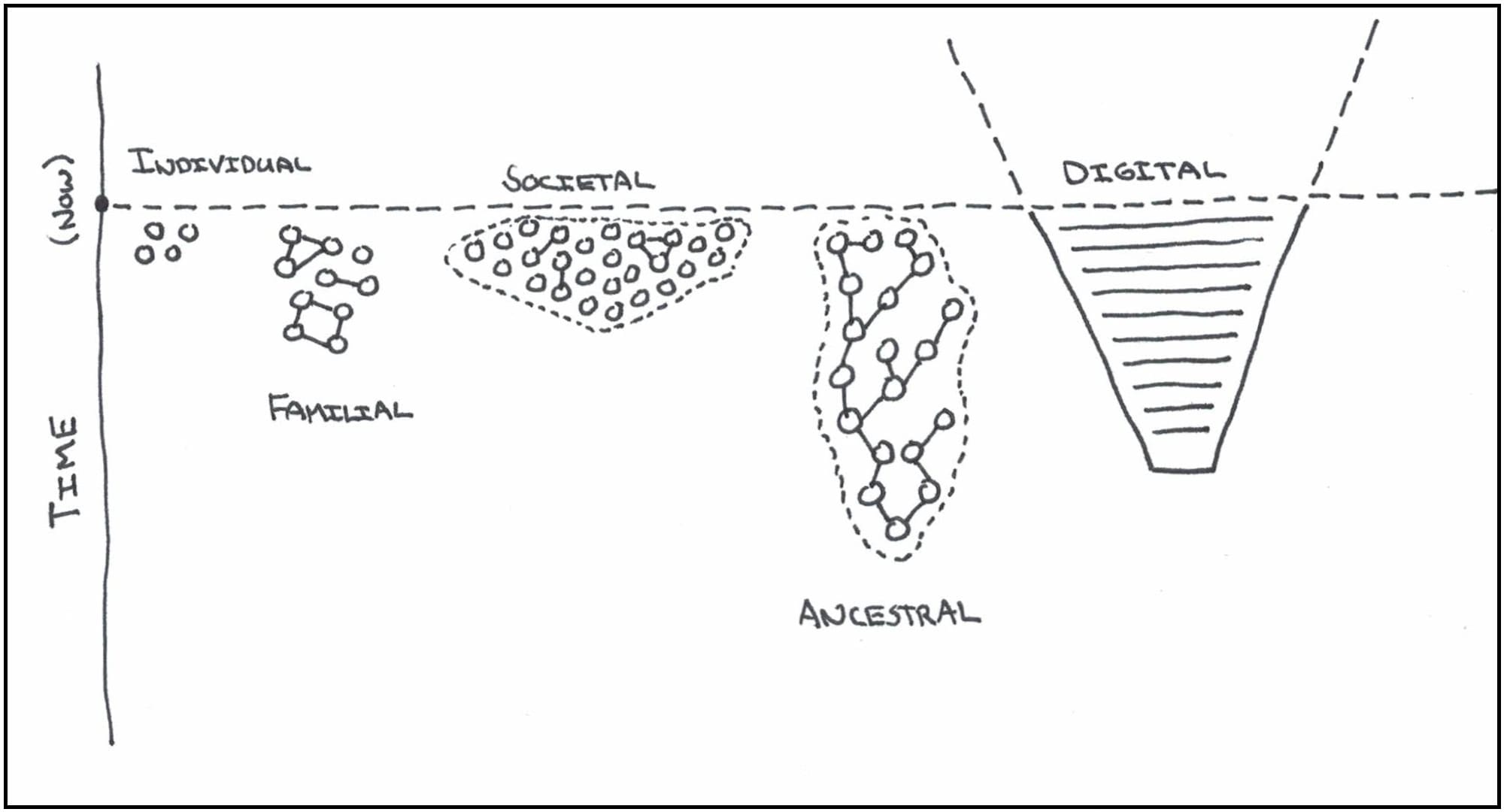

We view memory as an intensely personal experience. And it is, even if it is often shared with others. Memory comes in many shapes and flavors. Like molecules, memories combine in novel combinations to become something larger than themselves, evolving along individual, familial, societal, ancestral, and more recently, digital, lines. They take on new meaning and distinct attributes as they scale. Familial memories include the interplay between couples, families, and friends. They are the ties through time and space that bind. Societal memories are wide but shallow - they constitute our shared experience of events and form the basis of the cultural narratives we tell. We remember where we were when the Berlin Wall came down, or when we first heard the news on 9/11. Ancestral memories are narrow, but deep – passed down through generations. They are the mythologies we construct over time.

Finally, digital memories constitute a more recent, technological, entry into the space. Unlike its more organic cousins, digital memory consumes information, not events. This information is stored in the RAM, disks, and caches that make modern computing possible. The digital configuration represented by modern generative AI capabilities is perhaps the most intriguing, and it is this ever-hungry symbiosis of information and algorithms that threatens to disrupt the balance of our more organic memories.

One way to think about AI is as a consumer of memories - of our collective societal and ancestral memories. Generative AI is the apotheosis of digital memory, in that it doesn’t simply recall information verbatim, it lends its own interpretation, guided, to a degree, by the prompts of its users and handlers. We continually feed it from a well of information generated through the collective memories and efforts of mankind, and it greedily consumes these memories, resamples and reinterprets them, and provides them back to us in some simulacrum of the original.

While impressive at first, the low-hanging fruit is nearly picked. What happens then, when this well of memories is expended? When the information runs low, but we continue to demand improvements from our tools? As AI is forced to train itself on AI-generated content due to a dearth of human-generated content, it risks regressing to a low equilibrium. We’ve seen much hand wringing over this scenario, and while plausible, I sense that high-end AI models will always be able to afford purchasing high-quality human training material, while low-end commodified models will be the ones that most suffer from this regression.

Both digital and human memories are selective – but digital memories are consciously so, while human memories are more likely to do so subconsciously. That is, digital memory expends terrific resources to interpret what is important, and what is relevant. It must focus on storing vast amounts of information, because it is not immediately sure what will be most useful. It must also compress this information into reductive themes, to optimize for recall. But ultimately, that which is most important, most useful, is in the eye of the beholder. This is why human memory has tuned itself, over millennia of evolution, to be selective. We filter much of which is mundane or lacking in perceived future value. This imperfect capture is part of what makes human memory so alluring – ephemerality is a feature, not a bug.

One way to think about AI is as a consumer of memories

Because, if memory were to become all-encompassing, would it cease to be memory, and instead become something else? If it becomes immutable, if we lose the capacity to alter it, does that provide a better record of the past, or is something of personal agency lost in our ability to dictate the past on our own terms? Once chance is replaced by rules and random number generators, do we lose something of serendipity? Or, if the rules can be fine enough, and the random number generator just granular enough to simulate reality, does it really matter?

Part II: The Energy of Memory

To exercise a memory is to mythologize it, and mythology is one of the bedrocks on which we construct the narrative of the self. This narrative becomes our reality. To put a further point on it, those memories that we exercise are those that become our past reality. We retain a degree of control by choosing which memories - consciously or not - we exercise.

Here's the funny thing. If you don't dust off a memory and take it for a walk every once in a while, it atrophies. It's difficult to exercise a memory. It requires meetings with friends. Hours spent laughing together over drinks. Personal solitude without distraction. Dedicated time to reach out to family and friends. And during those times, there must be space for reflection, for nostalgia. The more we age, and the broader the scope of our memory grows, the more difficult this becomes.

Memories are malleable, but that doesn’t in any way diminish them. Rather, this flexibility lends a degree of freedom to the memory holder to revisit memories from different angles, returning with new information, experience, and perspective after years spent wandering. They stay with you, and become, as Hemingway writes, a “moveable feast”.

So then, let us exercise a memory. One of walking through a field, the crisp late-summer grass crunching underfoot. The susurrus of a nearby stream eliding over the smoothed rocks beneath. But the sky is blank - what did the clouds look like? Wispy like a stretched cirrus, or puffy and cumulus like those slick river rocks? You may have forgotten, or rather, you may not have formed the memory. And so the act of exercise is one of interpolation. In your mind, the clouds suddenly become soft and fluffy, and the day fills in around it as the threads of memory coalesce.

Some memories are weightless gifts that travel with us without fear of baggage fees or confiscation. They take up residence in our minds, buoy us in times of despair, and urge us on in moments of need. Others are the heaviest burdens we could ever hope to bear, anchored deep with no expectation of release. Exercising a memory should ideally be an act of reflection and introspection, though a more cynical revisionism is never far from the surface. Both options are available to us, the yin and the yang of human agency.

There is great benefit to us as individuals in being able to harness and alter our memories. There is correspondingly great danger to us as a society in allowing AI to alter its collective memory. Right now, that process of alteration is informed by humans – by people deciding which guardrails are necessary, which responses are accurate, and which content is troublesome. That is, they are exercising the AI’s memory by reinforcing which memories are good and which are bad, which are right, and which are wrong.

The reality of the present is constructed by the memory of the past – or in more Orwellian terms, “who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past”. This selective recall is an important aspect of the power of AI, and as the scale of AI’s digital memory grows, so does the power accorded to those implementing this recall. When that selective recall becomes untraceable - hidden behind profit motives or shaky moral compasses, it becomes a danger to our reality. When the only truth for those in power is “I must remain”, then digital memory will be twisted to uneven ends, becoming a distortion of our collective heritage.

In a world saturated by technology, retaining control over the kingdom of your mind is a necessity. We should better teach the value of memory if we hope to launch insightful future generations. We can outsource the triggers of memory to our devices, but we should never outsource the memory itself. Photos, music, writing - these are all mnemonic devices to help harvest crops of memories from the fields of our minds. And nurturing these triggers, over time, is one of those life skills that is rarely taught. It is something that is chalked up to "experience", "good parenting", or "healthy habits". But no one teaches you to revisit your memories. Sure, you may hear platitudes on training your memory for better recall, or improved mindfulness. But there is a distinct lack of focus in early schooling on the development of healthy meta-habits – memory, discipline, awareness. These are skills, like any other, that must be nurtured early.

Part III: Conclusion

I've carried in my head over the years the notion of a "memory book". It's a fable, of sorts, of a woman who starts writing one day in her memory book. She records the details of the day. The next day, she returns to the book but is stumped. What can she write about? Nothing new comes to mind, so she writes about her memory of writing in the memory book. The sky was gray. The next day, similarly stumped, she writes about her memory of her memory of the memory book. The sky was blue. And so on, et cetera. Over time, the core of her memory and her being becomes fully wound around this book, this single foundational memory that started it all, but from which she cannot run, and cannot break free. We are all often fixed in our thoughts and manners, and at times, as we make our own ledger entries in the memory book, we fail to see beyond what has been, and into what could be. Like petrified wood, we slowly ossify.

The introduction of small wrinkles can help us alter course. Those wrinkles need not have happened verbatim, they can be injected into the past. And perhaps that is what memory is - an interpretation of the past, for the benefit of the present and for the sake of the future. Originality requires those wrinkles. It requires the freedom to interpret the spaces in between, to make conscious choices. While we can post facto introduce those wrinkles by exercising our memories, we must also strive to introduce them into our daily lives to create the space for new memories to thrive.

It is both strange and natural that my father's little piece of petrified wood has been around for millions of years, and will continue long after I have gone, in exactly its current form. In the meantime, in the blink of an eye of human time, I can hope only that it serves to connect and to bond; a stony talisman that draws us closer together in an age where the acceleration of time seeks to do the opposite.

This then is one of the great perils of technology. Not that we forget how to recall facts and instead rely on the machines, but rather, that we distract ourselves to the point where we lack the time to exercise our memories. So then, practice the art of memory – of making them, recalling them, dancing with them in the quiet hours and the loud. These are the days that sustain – today, tomorrow, the next day. Memories must be made.